We invite you to read this essay carefully, not only because it is written by an expatriate woman who has found herself to deal with the culture she has married in a certainly not usual way, but because it makes us reflect on justice, respect, diversity and communities.

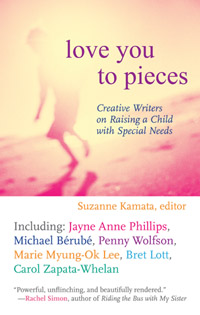

Suzanne Kamata moved to Japan where she married a Japanese, with whom she had two children, Lilia and Jio. We thank her for allowing us to publish this essay, taken from her book Love you to Pieces: Creativa Writers on Raising a Child with Special Needs (Beacon Press, 2008).

Living with Lilia

By Suzanne Kamata

Eighteen years ago, I came to Japan to teach English. I fell in love with and married a Japanese man who, before meeting me, had never been out of the country.

As a person who enjoys solitude, I thought I was well-suited to a Japanese marriage. My husband, Yoshi, worked seven days a week, up to twelve hours a day, teaching high school and coaching baseball. His job involved many evenings of eating and drinking without me.

In the early years of our marriage, when he was off with the teachers in his department or parents of his baseball players or other coaches, I had the evening to myself – time to write, or read, or to go for long, contemplative walks.

Although we took trips together, I was free to take off to Europe to participate in a writing workshop for a couple of weeks or to visit friends across the United States, on my own.

I’d always liked having autonomy in our marriage, even though I sometimes regretted not being able to entertain or attend social gatherings as a couple. Then we decided to start a family.

I knew that having children would be difficult in Japan. My sister-in-law, whose children were six and eight, told me that she’d never had a babysitter, and that the only time she was ever apart from her daughters was when she went to get a haircut. Most nights, her husband played mah johng after work, and didn’t get home till after his family was asleep. I found this hard to believe, and I vowed that things would be different after we had kids. I would have a life of my own. Yoshi and I would go out on dates. I would find a babysitter.

I knew that having children would be difficult in Japan. My sister-in-law, whose children were six and eight, told me that she’d never had a babysitter, and that the only time she was ever apart from her daughters was when she went to get a haircut. Most nights, her husband played mah johng after work, and didn’t get home till after his family was asleep. I found this hard to believe, and I vowed that things would be different after we had kids. I would have a life of my own. Yoshi and I would go out on dates. I would find a babysitter.

The premature birth of our twins, at 26 weeks, changed all that. For one, it immediately set us apart as a family in a very literal way. For the first four months of their existence, we were fractured. Our babies struggled along in their Plexiglas isolettes in the NICU at Tokushima University Hospital, where the doctors and nurses did most of the feeding (intravenously, and later, through gastric tubes) and changing of diapers. Only parents were allowed in that chamber of bright lights and beeping monitors. We had to have permission from the doctors and nurses to hold them. My mother-in-law wasn’t allowed to see them at all.

I longed for my peers – other mommies navigating the same terrain, with children who might become friends with mine.

When Jio and Lilia were both finally released from the hospital, our family went into isolation. The doctor warned us that a simple cold could turn into a life-threatening respiratory infection. He suggested the possibility of heart failure. It would take at least two years, he said, for their lungs to fully develop. In the meantime, we would need to avoid crowded places – supermarkets, restaurants, nursery schools, libraries, playgroups, birthday parties – all the venues where new mothers converge to share wisdom and reduce stress. Walks around the neighborhood were risky because there’d always be some bent-backed granny wanting to poke her finger into their plush pink cheeks. The world was suddenly teeming with germs.

My parents and other relatives were 14 time zones away, but my Japanese mother-in-law came over to help several times a week, resulting in the usual generational and cultural disputes. For instance, she wanted the babies to be swathed with blankets in the middle of summer, while I wanted them to be comfortable; she wanted to give them homemade carrot juice with honey, while I raged about the possibility of botulism. Still, I needed her help. I also called upon a battalion of older Japanese housewife friends, mostly women who’d faithfully attended the English classes I’d taught at the town hall, women interested in foreign cultures.

My parents and other relatives were 14 time zones away, but my Japanese mother-in-law came over to help several times a week, resulting in the usual generational and cultural disputes. For instance, she wanted the babies to be swathed with blankets in the middle of summer, while I wanted them to be comfortable; she wanted to give them homemade carrot juice with honey, while I raged about the possibility of botulism. Still, I needed her help. I also called upon a battalion of older Japanese housewife friends, mostly women who’d faithfully attended the English classes I’d taught at the town hall, women interested in foreign cultures.

In some ways, I remember those days as idyllic. Lilia and Jio slept through the night from the time they came home from the hospital. They took long naps, sometimes simultaneously, and I had all those helping hands, allowing me to go for walks or write. But still, I longed for my peers – other mommies navigating the same terrain, with children who might become friends with mine.

For a long time, I figured that this intense period of isolation would be followed by a more or less normal experience of motherhood. I believed that once my twins caught up, once their lungs had developed fully, they would have a typical childhood – one comparable to that of the many children I’d taught at public schools in Japan.

Jio and Lilia would not be able to go to school together, but would develop separate cultures.

Of course, we’d have our differences. My children would speak both Japanese and English. Instead of driving up to Kamiyama Shinrin Park or even Tokyo Disneyland during summer vacations, they’d jet off to America. And I was looking forward to seeing how that twin thing would develop.

My grandmother, who was a twin, often spoke about the special bond she’d shared with her sister. My sister-in-law spoke to her identical twin on the phone several times a day. Would my kids develop a secret twin language? Would they bond most intensely with each other, like the books said, making me a third wheel? Being twins, I thought, automatically gave each of them an ally. Sure, they might be bullied a bit in Japanese public schools, where everyone is supposed to look and behave in the same way, but they’d have each other.

I didn’t know then that Lilia was deaf and that her brain had been injured. I didn’t know that, because of her, our home would become a house of Babel, where we would use Japanese, English and Japanese Sign Language in various degrees of proficiency, sometimes translating for one another. Jio and Lilia would not be able to go to school together, but would develop separate cultures. One would start to walk and then run and then climb trees, while the other would drag herself along the floor with one arm until finally, years later, she learned to crawl. And instead of surrounding myself with older, supportive Japanese women interested in foreign cultures, I would soon be spending a lot of time with Japanese mothers of deaf children who viewed me as profoundly other. Now, no one ever asked for my autograph or invited me to appear on TV or threw parties in my honor. At the deaf school, I was simply the gaijin who had a hard time learning to finger-spell in Japanese, the klutz who didn’t know how to make tea. And I understood. These mothers didn’t have time to think about foreign cultures. They had problems of their own.

I didn’t know then that Lilia was deaf and that her brain had been injured. I didn’t know that, because of her, our home would become a house of Babel, where we would use Japanese, English and Japanese Sign Language in various degrees of proficiency, sometimes translating for one another. Jio and Lilia would not be able to go to school together, but would develop separate cultures. One would start to walk and then run and then climb trees, while the other would drag herself along the floor with one arm until finally, years later, she learned to crawl. And instead of surrounding myself with older, supportive Japanese women interested in foreign cultures, I would soon be spending a lot of time with Japanese mothers of deaf children who viewed me as profoundly other. Now, no one ever asked for my autograph or invited me to appear on TV or threw parties in my honor. At the deaf school, I was simply the gaijin who had a hard time learning to finger-spell in Japanese, the klutz who didn’t know how to make tea. And I understood. These mothers didn’t have time to think about foreign cultures. They had problems of their own.

One mother worried that her youngest daughter’s deafness would affect her hearing eight-year-old daughter’s marriage prospects. Other mothers lamented the fact that their children were not welcome in public schools. Although Japanese law requires disabled children to be educated, they are mostly limited to schools for the disabled. That is, unless the mothers are willing to spend months or even years lobbying for a spot in public school for their children.

It’s always the mothers. In Japan, child-rearing is shared by the mother and grandparents. The father’s job is to make money. The fathers are working till 11PM, or abroad on business trips for multinational corporations or off playing pachinko or drinking with co-workers. The teachers at the deaf school say that it’s harder for Japanese fathers to accept their children’s disabilities. Maybe that’s because they are so removed from the daily lives of their families. The mothers I’ve met at the deaf school clearly love their children and constantly advocate for them. But most of the fathers can’t even be bothered to learn sign language.

According to Japanese tradition, my husband, as the eldest (and only) son is responsible for taking care of his mother in her old age. Yoshi assured me when he asked me to marry him that his parents didn’t expect us to move in with them, but when we decided to buy a house, his mother confessed that she’d been hoping we’d all live together. I thought of my grandmother who’d blamed her divorce in part on her live-in German mother-in-law. I couldn’t imagine sharing a kitchen, a life, with my conservative Japanese mother-in-law.

However, a month after we signed the deal for our new house, my father-in-law was diagnosed with lung cancer. Another month later, he was dead, leaving my mother-in-law all alone in her large house. Yoshi’s Confucian ethics kicked in. From then on, he lobbied for us to move in with her. For ten years, my response was “hell, no!”

When I tried to teach her a few signs, she seemed unwilling to learn, but Lilia adored her. I gradually came to realize that Grandma’s reluctance to learn sign language might be a good thing. We were living in Japan, but I made many mistakes in speaking Japanese, and I can read and write at only a very basic level, I’d also have a little help around the house.

For awhile, I tried to be independent, taking my daughter to the deaf school and to her various therapies, doing research on the Internet, talking to other Moms. But after five years of spending almost every waking moment devoted to my children with no real end in sight I was ready for some respite. My daughter still couldn’t walk and although she’d had an operation for a cochlear implant, she couldn’t talk. She would obviously need me for a long time. At least my mother-in-law would be able to look after the kids for a small part of the day, long enough for me to make a run to the grocery store. And she’d be able to help with Japanese homework and occasionally babysit when Yoshi and I could arrange a date night. Also, and perhaps most importantly, with my husband gone all the time, there was no one around to model Japanese for Lilia. If we lived with her grandmother, whom she adored, Lilia would have incentive to learn the language. So, after ten years of “no,” I finally said, “yes” to living with my mother-in-law.

Yoshi’s idea was that we would sell our house and renovate his mother’s larger house, adding a small annex for her, where she would be assured a bit of privacy. Our new dwelling would be accessible and healthy – a haven for our disabled daughter. There would be a ramp for her wheelchair. The doors would slide easily open. The wallpaper would be resistant to bacteria and mold. The floors, where Lilia tended to crawl, would be heated in winter, and there would be bars on the walls that she could grab onto when she tried to walk. After his mother died, Yoshi said, Lilia could live in the annex, where there was a small kitchen and a bath.

I had been led to believe that my mother-in-law wanted us to live together more than anything, but she balked at first. She said that the neighbors would talk about Lilia. What would they say, I wondered. That she couldn’t walk? That she was deaf? That she couldn’t talk? All of these things were true, so why bother hiding them? I’d read that, according to traditional Japanese belief, a child’s disability was deemed to be due to the sins of the mother. Was it possible that my mother-in-law’s neighbors would think that we were tainted somehow? Could they be that superstitious at the dawning of the 21st century? If so, I figured they were due for some enlightenment.

How lonely it must be to always be hiding one’s differences

We moved in at the beginning of summer. Not long after that, I saw a girl wandering in the street by herself. She was wearing a red helmet, the kind worn by disabled children who are apt to fall down. I was stunned. Why hadn’t my mother-in-law mentioned this child? Did she even know that there was another disabled child living just a couple houses away?

Several months later, I set out on foot for the grocery store. I had gone just a few yards when I heard a familiar voice. I turned to see two little girls, siblings, who attend the School for the Deaf, my daughter’s school. They were visiting relatives – the people who live in the house across the street. Once again, I wondered why this coincidence had never come up in conversation. How lonely it must be to always be hiding one’s differences.

This is not the family I imagined back in Michigan when I was playing with my dolls

Pushing my daughter in her wheelchair to the grocery store sometimes feels like a political act. Here, look at her I want to say. I refuse to hide this kid. She is beautiful and smart and friendly. If you look at her enough, you will get used to the legs that don’t work, the magnet sticking to her head, the hearing aid nestled in her ear. Lilia demands attention. She smiles at everyone we pass, and, usually, they smile and wave back. I wouldn’t be able to hide her away even if I tried; she wants to be out in the world.

I like to think that we are promoting tolerance and social justice in this farming community, but sometimes I dream about bringing her back to the States where I believe we wouldn’t have to fight so hard. At the same time, I know that my daughter loves and needs her father and grandmother, and that she is a part of this culture. Lilia, who bows without thinking, who is endlessly folding paper into origami shapes, who adores kimono, is more a part of this country than I can ever hope to be.

she has taught us never to take anything about the body for granted, including the ability to breathe; that there is always something to laugh about; that there are worse things than being noticed by the neighbors; that you don’t have to be able to walk in order to dance

This is not the family I imagined back in Michigan when I was playing with my dolls, back in the days when my dad came home at 5:30 every evening and was home every weekend, and my grandparents lived in other cities. Our family life is sometimes messy and complicated, but it is rich. Living this way has opened my eyes to the possibilities of family. I once believed that my children would grow up and leave, but now I expect that we will be responsible for each other in one way or another until we die. And although my husband and mother-in-law may still be thinking that Lilia will be dependent on us for her entire life, I am imagining the ways in which she might be independent. Perhaps one day she will have a family of her own – a husband and children, or a group of caring friends who live together. Maybe they will be Japanese, maybe many different nationalities. Maybe they will be disabled, maybe not.

In the meantime, we continue to learn from living with Lilia. So far, she has taught us never to take anything about the body for granted, including the ability to breathe; that there is always something to laugh about; that there are worse things than being noticed by the neighbors; that you don’t have to be able to walk in order to dance. And perhaps most importantly, we have come to realize that there is no such thing as a normal family.