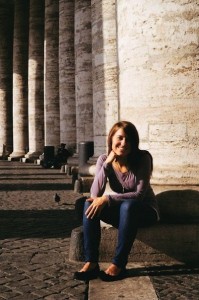

Jennifer joined the Expatclic family last year and she has become an active member of our Online support group. In this interview she tells us about her journey, both physical and emotional, of self-discovery. After leaving her native Michigan she travelled to Europe, lived in Italy at first before moving to Switzerland four years ago. Jennifer has always been aware of her mental and emotional complexity but it’s only since arriving in Europe that she has been able to identify it as “giftedness”. With this knowledge, she has developed a support network for those who, like her, feel at time a little “fragmented”. Thank you Jennifer for your honesty and generosity in sharing your story.

You were born in the US, live in Switzerland and speak Italian beautifully, I am interested in hearing more about it.

I lived in Michigan until I was 27. I had always dreamed of exploring the world, learning about other cultures and learning other languages, but it took a series of strange life events to give me the courage to make the leap! After traveling around Europe a bit, I ended living in Italy and absolutely loved it! I’ve been in Switzerland now for four years with my husband, but every time we talk about future plans, I always have one vote: Italy!

It sounds like you had the courage to follow your dreams! Did you experience any difficulties during that first period? Was the rest of the world as wonderful as you had imagined it?

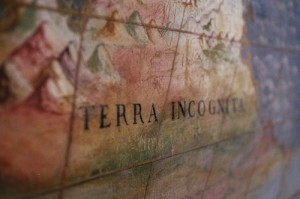

Yes and yes! Leaving the US for me was a mix between an escape and a dream come true. By many standards, I had built up a “good life” in the US, but I wasn’t satisfied. I felt stifled by conventional life, and unable to explore and express myself adequately in that context. When I left (which was an ordeal in itself), a lot of people were very angry with me and I went through a highly challenging period of social uncertainty. But I had gotten to the point that I could simply no longer ignore my deep inner need to explore the world; I had to discover other options for living, and other ways of thinking, being, and relating than the ones my American life had presented me with. I felt I needed a self-discovery journey.

Yes and yes! Leaving the US for me was a mix between an escape and a dream come true. By many standards, I had built up a “good life” in the US, but I wasn’t satisfied. I felt stifled by conventional life, and unable to explore and express myself adequately in that context. When I left (which was an ordeal in itself), a lot of people were very angry with me and I went through a highly challenging period of social uncertainty. But I had gotten to the point that I could simply no longer ignore my deep inner need to explore the world; I had to discover other options for living, and other ways of thinking, being, and relating than the ones my American life had presented me with. I felt I needed a self-discovery journey.

That’s what the rest of the world offered me: options! New ways of looking at things, alternative ways of thinking and relating, and better social mirroring. For example, meeting other expats with the same wanderlust helped me see that my unconventional desires are much more common and “normal” than I had thought.

Living in Italy and learning to speak Italian was transformational for me! I saw that il dolce farniente is okay, and that I didn’t have to be as linear and accomplishing as I had always believed. I learned via the Italian language that I didn’t have to personalize things so much. Linguistic differences as simple as the distinction between “I’m cold” and “ho freddo” (I have cold) really changed my perception of the nature of the self, and the nature of reality. I had gotten used to seeing things only from the standard American point of view, and within the confines of the English language where the “I” reigns supreme.

It has taught me to balance out who I used to be growing up in America, with who I am now and who I am becoming.

These and other experiences and insights from my expat life helped me to find balance. As I learned to depersonalize experiences and found more social belonging, I felt freer to just be. I started to see the world as a wonderfully complex mirror; it is full of so many expressions and possibilities, which reflect back to me my own complex inner world, and the many possibilities of expression that exist within. So yes, the world is as wonderful as I had imagined it, but it has still pleasantly surprised me! It has taught me to balance out who I used to be growing up in America, with who I am now and who I am becoming. I feel now that I am a co-creator with the world rather than just a dreamer or a runaway. And I do believe that is why I always felt so called to get out there and discover “the world”!

I like your insight into the Italian language. I guess that, in Italian, “we are” emotional reaction (“Sono felice”) and “we have” physical reaction (“Ho fame”). I can certainly see how it can impact on ones perceptions!

You definitely went through a big transformation, what impact did this have on your career? You were a psychologist in Michigan, have you pursued that professional path since your arrival in Europe?

I became a psychologist more because of life circumstances than because of a strong personal choice. I had always had so many deep interests that it was impossible to choose between them all – music, business, language, culture, literature, biology, neurology, astronomy, cosmology, art, philosophy, and so on.

I became a psychologist more because of life circumstances than because of a strong personal choice. I had always had so many deep interests that it was impossible to choose between them all – music, business, language, culture, literature, biology, neurology, astronomy, cosmology, art, philosophy, and so on.

I had studied classical music and psychology at university, and was subsequently so torn between the two paths that I let life circumstances decide for me.

I continued on with graduate training as a psychologist, but once I started practicing, I found the traditional practice of psychology too slow for me and I did additional training as a life coach.

By the time I left America, I had already started a coaching business, a few other entrepreneurial pursuits, and had taken on different roles in the corporate world, including some leadership roles.

I was doing a lot and learning a lot, but when I left the US, I quit all of it for a time. My professional life had become like a closet that was too full of clothes: I really wasn’t sure what was there because I wanted it, and what was there simply because of life circumstances. It was time to make the strong personal choice I had deferred during my studies. That was hard, because I realized that in order to choose, one must give up other options.

Gifted people have a lot of mental complexity and/or emotional complexity and intensity, which is sometimes wonderful, and sometimes quite a burden.

Since I’ve been in Europe, I’ve looked for a way to bring all my passions (or as many of them as possible) into one life: being an expat and working as an entrepreneurial and leadership coach, I have been able to work with people from all over the world (cultures, languages), in all different domains (business, culture, art, music, science, philosophy, etc.), and I’ve still been able to use my psychological insight in helping them – so all is not lost! I’ve also drawn heavily on all of my divergent interests in my writing (I’m about to publish a personal story based on my own journey – a more psychological version of Eat, Pray, Love; and I’m writing a book about giftedness as well).

My latest project – InterGifted – is another version of creating unity within diversity. I’ve learned since coming to Europe that I am “gifted”, and though that might sound arrogant, I assure you it is not. Gifted people have a lot of mental complexity and/or emotional complexity and intensity, which is sometimes wonderful, and sometimes quite a burden. I used to think I was a bit (and sometimes very) crazy, and I sometimes felt very alone, even though there were lots of people in my life who I loved and who loved me. I felt alone because my mind never sleeps, and I’m very highly sensitive to things that a lot of people aren’t; people around me often don’t understand why I keep thinking all the time and why I am so deeply affected by things that they don’t even seem to notice. I’ve often felt that I exhausted the people in my life with all of my curiosity and intensity.

I’ve met many others with intense minds, and now I know that while I’m not “normal” compared to many, I’m quite “normal” when compared to other gifted people.

But learning about giftedness, in some ways, saved me, because I learned that I’m not crazy or alone, it’s just that I process things differently than the “normal” linear way that a lot of people do. And I learned that statistics suggest only under 10% of the population have a “gifted” mind construction. When I learned that, I thought, “Oh, no wonder!”

Combining this knowledge and awareness with my work as a coach, I came to specialize in working with gifted people, and finally, I found my fit! Knowing what it’s like to be in that kind of mind, and knowing the particular demands and social needs of gifted people, I have found a way to connect my life’s work to the right “audience”. I’ve met many others with intense minds, and now I know that while I’m not “normal” compared to many, I’m quite “normal” when compared to other gifted people. That might sound strange, but it feels really good to feel normal sometimes!

In my experience, there is actually a high correlation between expats and giftedness.

And that is why I created InterGifted. To help gifted people around the world connect and experience the kind of helpful social mirroring I’ve experienced in my work. It allows that “less than 10%” of the population to meet their peers who have struggled hard to choose between their wildly divergent interests, who think way far outside of the box, and whose minds never sleep either! And it allows them a creative platform where they can work together, co-create, and support each other in meaningful ways. It’s not by any means a substitute for a person’s social or professional life, but a very helpful and meaningful addition to it.

It’s inspiring to see how you managed to put all your passions together and create the perfect job!

With InterGifted you are addressing “less than 10% of the population”, definitely a niche market. I am sure many of the expat women reading us today “think outside the box”, have a “mind that never sleeps” and “wildly divergent interests”. After all they have had the courage and desire to leave the known for the unknown and many of them had to totally reinvent themselves.

With InterGifted you are addressing “less than 10% of the population”, definitely a niche market. I am sure many of the expat women reading us today “think outside the box”, have a “mind that never sleeps” and “wildly divergent interests”. After all they have had the courage and desire to leave the known for the unknown and many of them had to totally reinvent themselves.

The term “gifted” is widely used in the US but perhaps not all of our readers are familiar with it. Could you tell us a bit more about the difference between having an inquisitive mind and a restless disposition and “being gifted”?

It’s a great question! In my experience, there is actually a high correlation between expats and giftedness. A lot of my gifted clients over the years have been expats, and for my clients who still live in their home country, living or extensive travel abroad is often a lifelong dream.

Expats who leave their home country because of an intense desire to explore the unknown (rather than because of economic factors, for example), are certainly not the norm. Expats in general make up only 0.72% of the world’s total population (just under 10% of the total population of developed countries). Do those numbers look familiar? A little bit like statistics on giftedness (which go as low as 2% of the population, according to some measures)!

I’m not confusing correlation with causation, as many people leave their home country due to family issues, war, economic factors and other reasons that have nothing to do with a sincere desire to explore the unknown; and many highly inquisitive people live in their native country their entire lives. However, among the 0.72% expat group, there is certainly a portion of expats who are drawn to and choose their expat life because of their intense curiosity, need for challenge and “out of the box” thinking. These individuals will likely identify with the characteristics of “giftedness” to some measure.

Recognizing giftedness is more like recognizing variations on a theme (think of Mozart’s or Bach’s Variations) than looking for carbon copies. The “theme” is: higher than average complexity and intensity. The “variations” are: intellectual curiosity, emotional depth, creative imagination, and physical skill, among others. While extreme curiosity about mathematics and language, for example, would be one variation (complex, intense intellect), high artistic sensitivities would be another (complex and intensely creative imagination); yet another is highly intuitive understanding of others’ feelings (complex and intense emotional depth). Usually, we see some combination of these “variations” in each gifted person.

This begs the question: what constitutes “higher than average complexity and intensity”? Most people are curious to some extent, so what differentiates – as you ask – the inquisitiveness of a non-gifted mind from the “higher than average” inquisitiveness of a “gifted” mind? Some people are a bit curious (low intensity) and want to know a few details (simple information), and some people are curious almost to the point of obsession (high intensity) and can’t rest until they know all the details (complex information). Think about the friend or the child who never stops asking complicated questions, and wanting to understand more: that’s a gifted person.

Of course, like everything, this is all on a scale – from “moderate” to “profound” giftedness. Many people deny being gifted because they are not profoundly gifted (“I’m no Einstein!”), but that doesn’t mean they are not gifted at a different “place” on the scale, with a different “variation”. As I teach in my work, it’s not about being Einstein, it’s about understanding the way your own mind works and being able construct a good life based on that.

I’ll just briefly mention that while it’s true that giftedness is more well-known in the US, it’s still rather limited to the educational realm. There has historically been very little support for gifted adults, but I’m happy to see the number of professionals dedicated to this is growing fast, not only in the US, but throughout the world. Part of my own work is mentoring these professionals globally.

Thank you for your clear and comprehensive answer, Jennifer.

I understand that being “gifted” comes with its fair share of issues and this is why what you have created is so important. InterGifted offers the opportunity to gifted people not only to share and connect, but also to deal with some of these issues.

To conclude, could you tell us, in your experience, what are the most common problems that gifted people have to overcome to live a fulfilling and happy life?

Understanding the problems that gifted people overcome is actually very similar to understanding the problems anyone (gifted or not) has to overcome in life. We all have to find enough self-understanding to be able to love and respect ourselves, and to live our life according to our own self-chosen values. Equally important, we all have to find enough social understanding and positive social mirroring to feel that our individual self and our authentic values have meaning and purpose in our social world.

It’s just that these life challenges are often “extra” difficult for gifted people. It can be really hard at times for a gifted person to understand the extent of the complexity of her own mind (too much thinking, overanalysis, feeling of internal chaos) and her intensity (unusually high energy, drive and excitability).

It’s just that these life challenges are often “extra” difficult for gifted people. It can be really hard at times for a gifted person to understand the extent of the complexity of her own mind (too much thinking, overanalysis, feeling of internal chaos) and her intensity (unusually high energy, drive and excitability).

One 38-year old highly gifted woman who recently consulted with me (I’ll call her Amy) described her mind as “the moshpit upstairs” that she avoided looking at because it overwhelmed her so much. Not every gifted person is as overwhelmed by his or her complex mind as Amy is by hers, but in general, a gifted person’s complexity can be quite…well…intense!

Secondly, because of being such a tiny statistical minority, it’s “extra” difficult for gifted people to find appropriate social mirroring. Naturally, the majority of people will have a hard time understanding the gifted person’s way of seeing the world; and as gifted people usually report, they often feel that they irritate or overwhelm less intense and less complex people.

In fact, a gifted person’s ways of questioning the status quo, playing the Devil’s Advocate and turning convention on its head can be extremely disturbing for those who value tradition, routine, and predictability.

As such, gifted people often hear things like: “Just stop thinking so much!” and “Why can’t you just be satisfied?”. This results very often in gifted people holding back socially and sharing only a small fraction of what’s really going on in their minds. My client Amy described her real self as “tightly closed in a jar that she dared never to open around other people”. She, and many other gifted people then struggle to arrive at a happy and fulfilling life, because their social mirror reflects only a stunted and fragmented and version of themselves; they struggle to understand fully who they are and how their presence is meaningful in the world.

The goal with my coaching and mentoring work, and especially with my InterGifted project, is to help provide more complete social mirroring for gifted people, so they can see themselves “whole” and not fragmented; and with this, they can come to a better understanding of how their full authentic presence is meaningful in a social context. One of the main reasons InterGifted also offers a network of coaches and helping professionals and a peer-to-peer coaching network is that, after a lifetime of keeping their thoughts to themselves, a lot of gifted people struggle to know how to reach out in the first place.

Additionally, like anything else in a gifted person’s life, traumatic life experiences, mental illness, relationship problems, professional projects, and other regular life issues that everyone faces, take on an unusual complexity and intensity. Having help from a coach or therapist who is also gifted and knows the struggle, and who is trained on the construction of the gifted mind and how to best channel it, makes all the difference in finding the “right” support to help a gifted person advance forward on his or her path to living a fulfilling and happy life.

For more information:

To join InterGifted, come to our website and sign up with your email at the top of the page. Then you will be invited to our secret Facebook group, and you’ll get invites to participate in group events.

Of course, if readers have questions, they are welcome to email me at jennifer@rediscovering-

Interview by Barbara Amalberti (Barbaraexpat)

November 2015