For this special updating on Extra-ordinary Lives Abroad, I want to honor the memory of an exceptional woman whom I met in Peru when I was living there, and that sadly left us last August. Common friends introduced Maria to me, and we immediately liked each other. The little time we spent together in Lima was full of respect and cherishing. As you will read in the article, Maria was deeply touched by the destiny of the Ashaninka people, for whom and with whom she fought until the last moment of her life. Please help me remember her by taking a few moments of your day to find out what this group is undergoing in Peru.

Rest in peace, Maria.

Claudiaexpat

May 2013

Meeting Maria was certainly one of the most beautiful things that could have happened to me in those last months in Peru. She was an outstanding woman, who told me about her incredible life experience. I am glad to offer you this amazing story as my personal Christmas present…

Maria is a woman out of the ordinary. Not only for her life story which, as you’ll see, is very special, but because past 80 years of age, she has a fresh, open, curious and lucid mind. It was her lucidity and presence which impressed me, when I first met her. When after our first meeting I called her to interview her, she immediately remembered who I was (I, half her age, always forget lots of things!) and kindly gave me her time to tell me her very interesting story.

Maria was born in Parma, Italy, in January 1927. Daughter of an army officer, she moved from town to town during her childhood, until the war threw her into a nightmare: her father refused to fight for Mussolini and Hitler, and was sent to a concentration camp in Poland. Her brother, a young army officer, went missing, too. In their country house near Parma, Maria and the rest of her family were sure they would never see their beloved ones again. Maria told me the long story of how her father escaped death on many occasions and how he went back home reduced to skin and bones, but alive. A happy ending because her brother also returned, and life slowly went back to normal.

Maria started attending the faculty of Foreign Languages and Literature at the Bocconi University in Milano. When the moment came to write her paper in English, she decided to go to Cambridge in search for material. There she befriended an Austrian girl, and it was while visiting her in Innsbruck, some time later, that Maria met her future husband, a young German. “Imagine how my father might react at the news that his daughter was going to marry a German man, after all he had gone through during the war!”, said Maria, laughing. “We saw each other hiding for a period. I was working in Milan for an import-export company, and he lived in Munich. One day my mother found the strength to face the topic with my father, who agreed to the wedding”.

Maria moved to Berlin with her husband, who worked there as a university assistant. It was the end of the 1950s, and her loneliness was the same that all courageous women face when accompanying their husbands in the world. Maria had studied English and French, but did not know any German. Being unable to communicate with the people around her made her feel isolated and invisible. For several months she swung between the desire to go back to Italy and that of staying close to her husband. Then her children were born, a girl first, followed by a boy. Maria became a full-time mother, and when they reached school age, she decided to do something about starting to work again. Since she was a graduate in foreign languages, and had already taught English and Italian in a high school in Parma, she decided to try teaching. “When I asked whether I could use my degree to teach in Germany, I was told that my piece of paper had no value there whatsoever, unless I wanted to use it to light a fire. I felt really wounded, humiliated and outraged by such rudeness. It was a frustrating time, until one day I went to Paris with my children to visit a German friend who lived there. She was also unhappy about her situation of trailing after a spouse and she also could not find a job. Together we searched for ideas. Her husband, who was very supportive, made me understand that my only way out of this situation, would be to start studying again. He suggested Social Anthropology, and I fancied the idea! Anthropology is a science that studies disadvantaged minorities, and at that moment I certainly felt part of a disadvantage minority!“.

Maria moved to Berlin with her husband, who worked there as a university assistant. It was the end of the 1950s, and her loneliness was the same that all courageous women face when accompanying their husbands in the world. Maria had studied English and French, but did not know any German. Being unable to communicate with the people around her made her feel isolated and invisible. For several months she swung between the desire to go back to Italy and that of staying close to her husband. Then her children were born, a girl first, followed by a boy. Maria became a full-time mother, and when they reached school age, she decided to do something about starting to work again. Since she was a graduate in foreign languages, and had already taught English and Italian in a high school in Parma, she decided to try teaching. “When I asked whether I could use my degree to teach in Germany, I was told that my piece of paper had no value there whatsoever, unless I wanted to use it to light a fire. I felt really wounded, humiliated and outraged by such rudeness. It was a frustrating time, until one day I went to Paris with my children to visit a German friend who lived there. She was also unhappy about her situation of trailing after a spouse and she also could not find a job. Together we searched for ideas. Her husband, who was very supportive, made me understand that my only way out of this situation, would be to start studying again. He suggested Social Anthropology, and I fancied the idea! Anthropology is a science that studies disadvantaged minorities, and at that moment I certainly felt part of a disadvantage minority!“.

It was 1968 when Maria joined the university in Berlin. Her husband, an executive, was against this; he was scared. He feared that Maria, wife of a person who, as part of the ‘establishment’ embodied the evils against which students and workers fight, will be opposed and ridiculed, if not worse. She did not give up. She went back to study, and developed a passion for the subject. The relationship with students did not pose any problem. On the contrary. Maria was lively and curious, she studied Marx diligently, organized study and reflection meetings in her home, and in the end she managed to overcome her husband’s skepticism, and to involve him. Maria also attended a course on Peru. She became so interested in it that she managed to obtain a scholarship to go to Peru and do research on a topic of her choice. Maria is very interested in bilingual teaching. She went to Huanta, near Ayacucho. It was 1973 and the terrorism years had not yet started, though Abimael Guzman, founder of the Shining Path, was already active at the Ayacucho University. He was preparing for the fight, which would turn into years of blood, violence and misery for the most isolated Peruvians. At the time that Maria arrived in Peru, the agricultural reform was in full swing. She was lodged in the house of a land owner, who was the uncle of the future wife of Abimael Guzman, and who tried to convince her to go to Ayacucho to meet the charismatic leader. For a variety of reasons, Maria left Peru without meeting him, and later was glad about that.

When Maria went back to Berlin her marriage collapsed. A very hard period followed, Maria was depressed, couldn’t get herself together. She needed to find something to help her through this time and give back meaning to her life. When GTZ (the German cooperation agency) offered her the chance to go back to Peru to start a project of bilingual teaching, Marie accepted without hesitation, even though this could mean losing Italian citizenship to acquire the German one. At that time it was impossible to maintain a double nationality, and GTZ could only employ German staff. “Up to that moment I had managed with my Italian passport. And I am talking about the time when Berlin was split by a wall, it was not easy to go in and out without a German passport. The Italian passport made me feel close to the mass of immigrants that came from the south of Italy and worked in really hard conditions: To me it was important to keep it. But I had such a huge need to leave at that moment, that I agreed to taking the German nationality. I still remember when the German embassy called me in Lima, when I was already in Peru. The employee of the passport section showed my new German passport and asked me to show him the Italian one. I gave it to him with a certain reluctance, and in fact as soon as he had it in his hands he gave me the German one and kept my beloved Italian passport”.

When Maria went back to Berlin her marriage collapsed. A very hard period followed, Maria was depressed, couldn’t get herself together. She needed to find something to help her through this time and give back meaning to her life. When GTZ (the German cooperation agency) offered her the chance to go back to Peru to start a project of bilingual teaching, Marie accepted without hesitation, even though this could mean losing Italian citizenship to acquire the German one. At that time it was impossible to maintain a double nationality, and GTZ could only employ German staff. “Up to that moment I had managed with my Italian passport. And I am talking about the time when Berlin was split by a wall, it was not easy to go in and out without a German passport. The Italian passport made me feel close to the mass of immigrants that came from the south of Italy and worked in really hard conditions: To me it was important to keep it. But I had such a huge need to leave at that moment, that I agreed to taking the German nationality. I still remember when the German embassy called me in Lima, when I was already in Peru. The employee of the passport section showed my new German passport and asked me to show him the Italian one. I gave it to him with a certain reluctance, and in fact as soon as he had it in his hands he gave me the German one and kept my beloved Italian passport”.

From that moment Maria had German nationality, but her heart remained Italian, and the warmth that welcomed her in Peru was typical of what the Peruvians reserve for people of our country. Maria’s work focused on finding schools where she would start her project of teaching in Quechua or Aymara (native languages) and Spanish. Searching for schools in the most isolated corners of the country is not what most people would like, but Maria accepted happily, thus discovering the most hidden and charming places in Peru. She spent the whole length of her project, 4 years, in Puno, and in the end she realized she did not feel at all like going back to Europe. Peru had entered her blood and she felt deeply involved with the problems of its population. She therefore accepted another job in the field of bilingual teaching, but this time in the Amazon forest, with the Ashaninka (an ethnic group that strives to survive in the Amazons).

She was based in a small community along the Tambo River, which originates from the Apurimac River and turns into the Ene River, and is one of the main water courses in the Peruvian Amazon forest. Maria lived ten years in that community and in that little bamboo hut, built exactly like the ones in which the Ashaninka live, working actively on the project of bilingual teaching and getting to deeply know the Ashaninka. “My task was to implement bilingual teaching in all of its aspects”, tells Maria. “Contacting the school, convincing parents to send their kids, searching out the right teachers and producing simple school material. It is not easy to produce material for a non-graphic language. I looked for easy scenes to represent with drawings, but it was not that simple. I drew a parrot with a long tail, and I was reproached because the parrot the Ashaninka children are familiar with has a short one…I had to find familiar elements in their lives. It has been an absolutely interesting project, and equally interesting and fascinating has been living all those years with the Ashaninka. They told me their stories, they warned me about the dangers I would meet in the woods…their culture is very rich with monsters and myths, some very funny ones, and living in such close contact with them allowed me to get to know it deeply. I developed a real passion for the forest, I did not fancy going to Lima any more, and when I had to do it for work I couldn’t wait to be back to my Tambo River. All this lasted until Sendero arrived”.

Sendero Luminoso, the terrorist movement that during the 1990’s spread death and terror in Peru, chose the most isolated spots to carry out their missions. In the most hidden mountains and in the most secluded areas of the forest, they killed, ransacked, raped, kidnapped and went away leaving behind horrified and desperate families and communities. The day Sendero arrived at the community where Maria was living, there was almost no one with her. Many members of the community had descended along the river to run some errands, and left her alone with the teacher, his wife and a couple of others. Maria was lying on her bed and resting when she suddenly saw a gunbarrel poking through the bamboo leaves of her hut. She went out and found seven guns pointed at her. Sendero took her to the medical dispensary and put her on trial. Maria, supported by a strong burst of adrenalin, explained what she did in and for the community. “The only moment when I got really scared” she says, “was when the captain of Sendero asked the two Ashaninka that were with me whether I was treating them well or badly. He asked that in Spanish, a language they knew very little, so I was not at all sure they would understand the question. For a moment I was seized by sheer terror. The Ashaninka looked straight at me and said “Well”. I sighed with such relief I can still remember today! When the questioning was over, they took a part of the carton of cigarettes I had with me, and left”.

Sendero Luminoso, the terrorist movement that during the 1990’s spread death and terror in Peru, chose the most isolated spots to carry out their missions. In the most hidden mountains and in the most secluded areas of the forest, they killed, ransacked, raped, kidnapped and went away leaving behind horrified and desperate families and communities. The day Sendero arrived at the community where Maria was living, there was almost no one with her. Many members of the community had descended along the river to run some errands, and left her alone with the teacher, his wife and a couple of others. Maria was lying on her bed and resting when she suddenly saw a gunbarrel poking through the bamboo leaves of her hut. She went out and found seven guns pointed at her. Sendero took her to the medical dispensary and put her on trial. Maria, supported by a strong burst of adrenalin, explained what she did in and for the community. “The only moment when I got really scared” she says, “was when the captain of Sendero asked the two Ashaninka that were with me whether I was treating them well or badly. He asked that in Spanish, a language they knew very little, so I was not at all sure they would understand the question. For a moment I was seized by sheer terror. The Ashaninka looked straight at me and said “Well”. I sighed with such relief I can still remember today! When the questioning was over, they took a part of the carton of cigarettes I had with me, and left”.

But now, the community did not know what to do. Sendero had left signs of their passage; they had daubed the huts in red and put flags everywhere. Taking them off would trigger their anger, in case they come back, leaving them on could make the Sinchi patrol, based a little further south on the river, suspicious (the Sinchi was the special police force created by Fujimori to fight terrorism: they also were responsible for deaths and horrors in the most remote areas). Maria and some members of the community decided to go and stay in Lima for a while, at least until things became clearer. A decision that saved her life. Three days after her departure a second column of Sendero Luminoso arrived at the community, this time with anything but friendly intentions: they were looking for the “gringa” to kill her.

So Maria stayed in Lima, from where she followed, as best she could and with a lot of anguish, the events of the forest in that painful and difficult period. The survivors’ tales are horrific: the summary executions of Sendero are amongst the most cruel and bloody, many young were kidnapped and sent to fight, those who refused to go underwent abuses and tortures that are too extreme to be told. The Ashaninka tried to resist as much as they could, until they finally decided to resort to weapons and react. Maria recalls the visit of Emilio, head of all the Ashaninkas of the area, who somehow managed to get to Lima. Maybe he was seeking a sort of blessing from her, when he informed her that the communities of Ashaninka had decided to resort to weapons and push Sendero Luminoso back. And they managed. They are the only community in Peru that managed to resist and push Sendero out of their areas. Part of this fight is documented in the excellent book by Fray Mariano Gagnon, Warriors in Paradise, available in French, English and Spanish. A book I beg you with all my heart to read.

Maria developed an extraordinary empathy with the Ashaninka. She continued to fight for them, telling of their resistance, their values and the richness of their culture in any way she could, from Lima. She sat with them at the reconciliation table, years later, when terrorism was defeated, and people tried to find a way out of the horror of that time. To the question “what does reconciliation mean to you?”, the representatives of the Ashaninka sitting at that table answered: “to be able to look into each others’ eyes again” Years would have to pass before this happened. In the meantime the Ashaninka fought other enemies. Maria told me that at that time in the Paquitza Pango pongo (pongo is the point where the river opens a passage between two mountains) work was underway to build a huge dam for electricity production, which would flood at least five Ashaninka’s communities; communities that live in peace and harmony with nature. In the same area oil had recently been found, and this had immediately awakened unscrupulous interests: five wells for oil extraction were being built. As if all this were not enough, the timber companies penetrated more and more deeply in order to cut the precious trees that enrich their business, all of which was contrary to the philosophy and habits of the Ashaninka, who live in total respect of nature and in harmony with it.

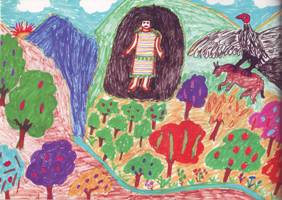

All this filled Maria with sheer anguish. At the end of the interview she asked me to speak as much as possible about the Ashaninka and of the slow destruction they face from the most complete indifference. She offered me a book of Ashaninka tales, with drawings made by the man that was her driver when she was living in the forest. Together we decided to use these drawings to illustrate the interview. We thus hope to give these wonderful communities a bit of space in the web, and, with our humble action, to draw attention to the very difficult conditions of continuous threat under which this group must live, a group of men and women as free as birds, who, far from progress and modernity, preserve one of the few treasures we still have: an untouched nature and culture.

Claudia Landini and Maria

Lima, Peru

December 2008